Digital transformation in government will require civil servants of all professions to pull in the same direction. Digital, policy, procurement, finance, analysis. All on the same page. But those groups often do not work in the same way. This slows us down.

One notable difference in approach is language use.

Take the digital profession. Digital in government has a particularly distinct lexicon. Hearing someone mention ‘user needs’ unprompted is a pretty accurate identifier of one of its members. Certainly moreso than owning a MacBook.

This profession is also packed with devotees of agile, favouring individuals and interactions over processes and tools. No surprise then that they have a plethora of terms to describe different types of discussion. Stand-up, sprint plan, inception, retrospective, futurespective, show-and-tell. All brilliantly useful. Once you know what they are.

Other government tribes have languages too of course. If you talk about ‘requirements’, it’s likely you are a member of IT profession. A mention of ‘key milestones’ outs you as a project manager. When I first joined the civil service as a policy professional I recall being asked to do a ministerial ‘sub’. As 50% New Yorker I couldn’t fathom how making the Secretary of State asandwich could possibly help.

The language issue feels important to me. As well as the misunderstandings it can lead to, it is a canary in the mineshaft of deeper divisions. So how could we improve things?

In the field of foreign language teaching, academic experts have long agreed that teaching a foreign language is much harder without also acknowledging the culture, i.e. the beliefs, values and behaviours, of the other. True understanding requires knowledge not just of words, but of words in their proper context.

Anyone who has talked at length about user needs to blank faces will recognise the problems caused by a lack of shared understanding of context. It may be possible for others to understand the words and the everyday meaning, but developing the reflex that if a user fails it’s our fault and not theirs does not happen overnight. ‘He/She doesn’t get it’ is a phrase one may hear among digital circles. But remember to our audience we can sound like the most naive of broken records.

Education professionals have thought at length about how best to learn about other cultures. Prof Mike Byram at Durham University has developed a series of ‘savoirs’ or competencies* for intercultural skills. Two stand out as particularly relevant to interdisciplinary working in government.

- Ability to evaluate perspectives in one’s own and other cultures.There are many teams who run services from a pre-digital spend controls era and have not encountered a new way of doing things through no fault of their own. What might we be taking for granted which we need to question?

- Readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and belief about one’s own. A former policy colleague recently remarked he felt he would be laughed out of the room if it was ever suggested that a policy person just might be able to do something useful in a delivery role. This perception has to change.

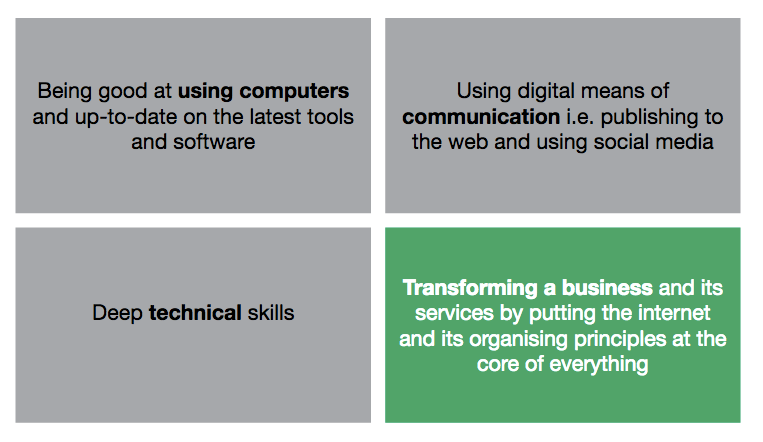

Beyond a shared understanding of language then, we need to share experience of digital culture: values of being user-focussed, open, sharing, collaborative, experimental, all underpinned and connected by the shared infrastructure of the Internet. The digital profession is better than many at demonstrating and sharing its values, but we shouldn’t let up.

At the same time, to foster better and quicker understanding and cooperation we need to see problems from other perspectives. Being good at this is not an innate ability but, as educationalists have shown, is a cognitive skill that can be learnt. In a collaborative era of transformation all professions may need to take skill building in this area more seriously.